Tribute from Pete Ayrton -

Tribute from Pete Ayrton -

Tribute from Naveen Kishore, Seagull Books, Calcutta -

Tribute from Bob Lumley -

Tribute from Bernhard Sallmann -

Tribute from Liz Heron -

Tribute from Rob Leiper, an old friend -

Tribute from Katharina Raabe

Martin Chalmers (1948-2014)

Ein Londoner Verleger nannte ihn einen “Botschafter der deutschsprachigen Literatur”. Tatsächlich lernt eine englischsprachige Leserschaft Werke von Elfriede Jelinek, Herta Müller, Hubert Fichte, Thomas Bernhard oder Hans Magnus Enzensberger in seinen vortrefflichen Übersetzungen kennen. Dabei wissen seine Leserinnen und Leser seine Bucheinführungen zu schätzen oder auch den fundierten kritischen Apparat, der seiner Übersetzung der Tagebücher von Viktor Klemperer anhängt (für die er mit dem angesehenen Schlegel-Tieck Prize ausgezeichnet wurde).

Doch die Tätigkeiten eines Botschafters lassen sich nicht aufs öffentliche Auftreten beschränken: Sein zuverlässiges Urteilsvermögen fand auch hinter den Szenen das offene Ohr so bedeutender Verleger wie Malcolm Imrie (Verso), Pete Ayrton (Serpent’s Tail) und Naveen Kishore (Seagull). Durch Chalmers’ maßgebliche Mitgestaltung gewann der deutschsprachige Anteil dieser unabhängigen Verlagslisten an Format. Konnten solche ‚Flüsterdienste‘ zu seinem Lebensunterhalt wenig beitragen, waren sie ihm als kulturkritische Intervention umso wichtiger – er war eben nicht nur „Botschafter“ der deutschsprachigen Literatur, sondern Anwalt ihrer besten Werke.

Einmal hatte seine differenzierte ‚Mission‘ sogar diplomatische Folgen: Als er von der Deutschen Schule in London eingeladen wurde, einen Vortrag über Erich Hackls Die Hochzeit in Auschwitz zu halten und dabei die Vorzüge einer marxistisch geprägten Tradition der „Geschichte von unten“ herausarbeitete, merkte er – sehr zu seiner verschmitzten Freude – wie der deutsche Kulturattaché ihm beim anschließenden Empfang demonstrativ die Hand verweigerte.

Martins Gewandtheit als Verlagsflüsterer und Übersetzer bildete sich schon früh heraus, wie übrigens – wohl gleichzeitig – seine Liebe zum Film. In Bielefeld als Sohn einer deutschen Mutter und eines schottischen Vaters zur Welt gekommen, flüsterte er schon der geliebten deutschen Oma (die Kleinfamilie war 1950 nach Glasgow umgesiedelt, seine Großmutter zog zwei Jahre später nach) während gemeinsam besuchter Glasgower Kinovorstellungen seine Dialogübersetzungen ins Ohr. Das Bedürfnis, die beiden Sprachen und Kulturen miteinander sprechen zu lassen, prägte auch fortan Leben und Arbeit. In Glasgow und Birmingham studierte er Geschichte. Weitere Stationen waren London und Berlin, wohin er 2007 nach Neukölln umzog – oder Rixdorf, wie er den Stadtteil nach einer älteren Namensgebung zu nennen pflegte.

Für Martin hatte dieser Umzug etwas von einem ritorno in patria, denn seine Großeltern mütterlicherseits hatten seit 1925 in Berlin gelebt. Sehnsuchtsvoll begab er sich auf die Suche nach jenem Bauernhof, wo seine Oma im ehemaligen ostpreußischen Angerburg (im heutigen Landkreis Węgorzewo, unweit der litauischen Grenze) als Dienstmagd gelebt hatte. Es heißt, er sei dort fündig geworden.

Ob in London oder später in Berlin zeigte er sich als besessener Stadtwanderer. Dabei zog es ihn – auch im Ausland – immer wieder zu Brücken (gleichsam Wahrzeichen seines Berufs) und Friedhöfen: dem Friedhof der Namenslosen, dem kleinen schottischen Friedhof in Kalkutta, auch dem Alten Matthäus-Kirchhof in Schöneberg, wo er unweit der Gebrüder Grimm seine letzte Ruhe gefunden hat.

Er war in den beiden letzten Jahren seines viel zu kurzen Lebens von Krankheit und Krebsbehandlung gebeutelt, doch in diesen Jahren besuchten ihn alte Freundinnen und Freunde, konnte er sich auf den liebevollen Beistand seiner Partnerin Esther verlassen, übersetzte er weiterhin Bücher von Peter Handke, Alexander Kluge und Sherko Fatah. Zeitgleich arbeitete er an eigenen kurzen Prosaformen: Memoiren, auch schonungslos offene, bisweilen humorvolle Schilderungen seiner Krankenhausaufenthalte. Für Gespräche über Literatur und Leben hat Martin stets hohe Maßstäbe gestellt: Das werden die Vielen, die ihm in Schöneberg das letzte Geleit gaben, schmerzlich vermissen.

Jacek Gutorow

My memories of Martin are minimal: a few hours on an April afternoon and a windy evening, almost one year ago. I still have a sense that the time was somehow unique. I felt its exceptionality when we were strolling around Neukölln (my only association of the place was with an instrumental piece by David Bowie) and sitting over black coffee and beer. Nothing serious. It was nice. Later, surprisingly, you lack words. You simply miss them.

It is difficult for me to write a decent tribute. The memory is so fresh, unsettled, unwritable. I find I cannot cope with words, sitting here in front of an empty sheet of paper. Here are some journal entries I’ve put together. For the time being these must suffice.

April, 2014

I met Esther and Martin at their Friedelstrasse flat. I knew that Martin (whom I saw for the first time) was seriously ill. What I immediately noticed was that he was discreet without being reserved and distant. I must say I was quite impressed by this combination. We talked about architecture, painters, Berlin galleries. I already appreciated the integrity and originality of Martin’s views and tastes. His intellectual independence was immediate and spontaneous, or at least this was how I perceived it. What a freshness of mind, I thought.

Later we took a rather long and meandering walk towards Landwehrkanal and Görlitzer Park. It was beautiful, the weather was perfect, the air transparent. Martin talked slowly, almost cautiously, and you instantaneously recognized a unique presence. We talked about poetry. Again, I found his tastes quite autonomous. Surprisingly, he mentioned Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” (who reads Arnold these days?). I told him this was one of my favourite poems. I realized I would remember Martin by this poem:

the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new…

It was Berlin. It was April 2014. But things don’t change that much.

October, 2014.

An email from Esther. Martin died yesterday. My first thought was: it’s unfair. But afterwards I lacked words, as if a part of my brain, the one responsible for using language, was blocked. In situations like this one feels like having to refer to someone else’s formulations, hoping that they would resonate and undo (unfreeze, rather) buried words.

As a matter of fact, I’d just been reading Ernst Weiss’s The Aristocrat in Martin’s translation. A most beautiful translation. Some startling parallels came to my mind, a few images centered around a premonition of death (this is a novel about death). Boёtius von Orlamünde, the story’s main character, has an unusual passion for the minutiae of the natural world. The English translation was crystal-clear and I realized not every translator would be capable of describing reality with such precision and care: “I see reflected the lake or the foliage, half blue, half green, only an illusion, only a moment, a gleam. My horse begins to sweat, and the skin darkens first at the edges of the harness, then the little hairs stick together, stand up in rows, as if they had been groomed with a wide-toothed comb. Now there’s a smell, heavy and aromatic, of sweat, of firs, rain and dust.”

The most moving passage comes a few pages later, though. I’d underlined it some weeks earlier, put a small sign next to it, a kind of five-pointed star. It was with those words that I addressed the sad fact of Martin’s death: “I told of the night, of my sleeping badly. It is not the dreams of youth, sick with longing, which wake me, which make me press my ear against the door of the neighbouring dormitory… what excite me is something quite different. Something else makes me get up and, my shoulders hunched, press myself first against one then against the other useless, tall lectern. It is a feeling that one will not suspect in a seventeen years old. But will one believe that this feeling, which I must name only too soon, has been active in my soul since it was a soul, for as long as I can remember at all? I must name it – but I am afraid even of the words. It is fear of death.”

January, 2015.

It was an early morning in Berlin, the first thing I did was checking the internet and reading some tributes addressed to Martin. People who’d known him well and managed to evoke his presence as if he was still alive. Memory in language, memory of language. Words soothe but first one has to find them, I thought.

After breakfast we visited the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof cemetery. In my journal I wrote: “The grave is situated in the shadow of a tall tree and I suddenly find myself trying to recall the name of the species of tree. It is bare, no leaves, just black bark. Stands there like a small cathedral. We light a candle. There is no wind. Just a quiet noon with grey clouds, a coal light. We are surrounded by graves with colourful decorations. A Jewish grave with white pebbles in a jar. A child’s grave with toys and little pumpkins. So many objects for the eye. Martin was telling me of Dutch painters and those miniature still lifes they rendered so wonderfully. So I guess he would love this place here.”

Tribute from Alexander Schmidt

Dear Martin,

We hardly ever talked about Johann Gottfried Seume. Walking as an all encompassing way of being en route in the world was too self evident for us to make a reference to him as we were striding along or breaking our journeys to eat and drink. But now, for everybody, an addendum: Seume, who walked from Leipzig to Syracuse and returned via Paris, full of praise for his cobbler, wrote in „My Summer of 1805“ : „He who walks sees on average more, anthropologically and cosmically, than the one who drives. … Where there is too much driving things don’t go well, just look around you! As soon as you are seated in a coach, you are removed from original humanity by a few degrees. You can’t look anybody in the eye any more with a firm and clear gaze as one should…. Driving indicates powerlessness, walking indicates strength.“

Martin, your solid shoes, your firm, reserved but occasionally also buoyant, even joyful stride. Places opened themselves up to you, you have the ability to walk on, regardless of potential boundaries.

Martin, you are a „wanderer“, wandering in urban space rather than in landscape. You never even mounted a bicycle. You as a driver of an automobile – inconceivable! With you I could walk my familiar Berlin and see it in a different light. Every passage way, every courtyard, every strip of wasteland, every housefront, every cemetery, every ornament, every faded sign, every bar – they all meant something to you. They gave you pleasure.

We wondered how many horses might have been around in Berlin after the Second World War. Where they would have been stabled, where they got their feed. When did the horses disappear from the cityscape?

Before you moved into Schöneweiderstraße in Rixdorf you asked me, to my bafflement, to show you the the cellar. You tried to imagine how many people would have been squatting there in the nights when the city was bombed.

You are earthed in the past, and your roots go deep.

You are a very polite person. Listening, appreciating. But with very firm principles. „Peace to the shacks!“. The new Berlin takes a different view. The shacks rather than the palaces have always been your dwelling place, as they’ve been mine. Our views are alike.

We will continue our exchange, dear Martin!

Bernhard

Five little memories of my dearest friend.

1 He liked animals. Cats in particular. After all, he helped Esther transport three of them right across Mitteleuropa, from Hungary to Berlin. But animals in general, really. I re-read an email he sent me at the time when he and Esther were giving up their little ‘dacha’ outside Berlin. He wrote: ‘I really enjoy the walks around here and expanding with Esther’s help my very limited knowledge of flora and fauna. And it’s been a great pleasure to watch things change over the seasons. Lots of fauna, for sure, from shiny beetles to exotically coloured lizards to, um, snakes (Esther doesn’t care for them so much), moles, racoons, deer and wild pigs (I’ve seen all the rest, but only heard the pigs and walked rapidly in another direction). And the birdies! Migrating swans and geese (and the geese in the farmyard across the track, waiting patiently and trustingly for Christmas) herons, trumpeting cranes, not forgetting the storks, orioles and numerous kinds of birds of prey, oh and not forgetting either the noisy frogs. Further to animals: Did you ever have anything to do with Karin Duve? [novelist] She lives in this hamlet, we nod as she rides by on her white horse, she also has a donkey, which she saved from being turned into salami. I’ve never actually had donkey salami, tho you can buy here and there. Horse salami a few times and I’ve got a goat sausage in the fridge at the moment.’

2. He liked raspberries. He was a small-time gambler. I have a vivid memory to prove it, which must date from November 1994 because that is when the National Lottery was launched. Poor as church mice, as ever, we were walking down a London street (but which and why?) and he told me he had bought one of these new lottery tickets. And we went and checked in a newsagent and he had won. Beginner’s luck, huh? Ten whole pounds. So we came out with this substantial sum and there was a greengrocers next door. He stopped, and took a punnet of raspberries from the stall outside. Said it seemed like the best way to spend his winnings. Raspberries in November? Must have been imports. But I expect there was some change and I expect we spent it on beer.

3. He liked shaving. I think. At least, it seemed to be a very important ritual, often postponed until surprisingly late in the day. He told me that even if he’d been out late or had a hangover, he would always get up by a quarter to eight. Otherwise he would be a waster. He was firm about this, and I have adopted it as a rule myself. But then there seemed to be a big gap before the shaving, in which he would work; and we would often talk on the phone during this period, which is how I know about it. Many of these talks were about books, especially when Martin was reshaping Verso’s German translation programme, quietly and persistently; I was the inhouse editor, and most of the time he would be suggesting ways I might persuade the editorial board that this was an important and commercially viable book to translate – he had already convinced me, at least about the ‘important’ bit, as he always did. I am assembling a list of Verso books owed to Martin; the first I recall is Fritz Kramer’s The Red Fez. But eventually Martin would tell me he had to go and shave. This would be around noon. If I asked him why he bothered so late in the day he would say: oh, I might go for a walk.

4. He liked clothes. A difficult interest to indulge as a freelance translator, let alone a freelance literary translator, and today it would be quite impossible. But he found ways . . . For example, he introduced me to the Paul Smith sale shop in Avery Row. Though even that was often out of our range. I have long lost track of the fashion in this matter, but he also introduced me to the idea of doing up the top button on a shirt. Martin always offered the world a bella figura, and not just with his natural good looks. Now, he certainly never judged people by what they wore . . . but it was a factor to be taken into consideration. As with everything else, I took his firm but gentle judgements very seriously. When I stayed with him not long after he moved to Berlin (I think the only time we spent some days together under the same roof), I wore (and I hadn’t much choice at the time) the best, most expensive and oldest pair of ankle boots that I possessed. Dark brown leather. And as I was putting them on, one chilly morning in his flat, among lots of still-unpacked boxes, he said they were great boots. They are now about 25 years old and I keep them for special occasions. (I should add that, on the other hand/same feet, he hated my accompanying socks. ‘Oh no!’, he said. I have kept the socks but have never worn them since.

5. He liked films. Oh, he did! And he was, I think, one of only two people, whose judgements on a film I have always trusted, and been grateful for trusting. His knowledge of cinema was boundless, as we all know. As much as of books, or music, really. I only disagreed with him once, on the brown-boot Berlin trip, when we went to see Le silence de Lorna directed by the Ardenne Brothers. It was the first of their films I had seen. I disliked it. Martin liked it very much. We argued, something we hardly ever did – or rather I ranted and Martin calmly, gently, firmly, defended it: then we forgot it with half a chicken and a fair bit of beer each in a café whose name I wish I could remember. I have been wondering since then whether I shouldn’t perhaps see Le silence de Lorna again. A year or two ago, I saw Olivier Assayas’s film Après mai (‘Something in the Air’ in English) and liked it very much. So much so that I had to know Martin’s opinion, especially because it was about the far left in France in the early ‘70s. And because politics, of course, was what we shared most, perhaps where we were closest. So, this kept troubling me. I feared that in fact Martin might hate it. I tried to rehearse all his objections, see if I could answer them. A soundtrack featuring Kevin Ayers, Nick Drake, the Incredible String Band (twice!); for starters. Hmm. And then, after I came back from his funeral in Berlin I spent some time rereading his old emails. And in one dated 26.6.13, there it was, short and sweet, I’d forgotten. I quote: ‘I enjoyed Après mai, which seemed to find some of the London critics in grumpily reactionary mood’. I think he meant silly Peter Bradshaw. So now I am sure. Good. Go buy the DVD, it’s a gem!

For a publisher, Martin was the best friend and guide you could have. His literary judgements were always pertinent and given in a spirit of informed scholarship. Martin never allowed his likes and dislikes to be clouded by the demands of the market-place. He rightly left that job of mercantile compromise to the publisher. In the years that he advised Serpent’s Tail, we published on his recommendation two Nobel Prize winners, Elfriede Jelinek and Herta Muller and other extraordinary writers like Hubert Fichte and Ernst Weiss. An afternoon spent talking with Martin was a cornucopia of treats – if you let the conversation go the way he thought it should, you would be rewarded by insights usually relevant and always stimulating. His own writing, of which there is unfortunately too little, was like his conversation a delightful meander in which personal experiences were located in a larger historical picture. Rarely was learning so rewarding an experience.

He is already missed. Pete Ayrton

Tribute from Naveen Kishore, Seagull Books, Calcutta

Tribute from Naveen Kishore, Seagull Books, Calcutta

Difficult isn’t it? Hard. To mirror-map your steps. Dear guide. To walk these streets in the same way you and I did. Once. More than once twice thrice. In fact. Every single time I went to Berlin. Or at least remember what it was. That felt good. Those winter days of sleet-rain and cold-wind and an unprepared-me. Blindly following you. The snow struggling beneath my feet to assert itself. The soles of my shoes unsuitable for the ice. Slippery beast. Fighting a losing battle while you strode confidently. Forward. Saying it was just a little more to the park. The airfield. The cemetery. The church. Or the remnants of a wall now abandoned. Not wanting to let you down I kept pace. Enjoying every moment. As we tramped Berlin. Armed only by the frosty wind. And our conversation. The ones that began elsewhere. Somewhere. Everywhere. Anyplace but this. And didn’t end. Though we reveled in the silences. They. Like our breathing. Had much to talk about. Often our thoughts needing to be heard. In immediate and simultaneous excitement. Uncontrolled. Speaking together. We would smile and say a polite after you. Secretly wanting to be the first one with the fresh idea. Wipe the rain off our glasses. Revealing a shared twinkle. And carry on in one philosophical direction or another. In one political vein or another. Or simply enjoying the shared literature we were planning to inflict on an unsuspecting English speaking world.

It will be hard. But soon it will be time. To walk. Yes I will walk the Berlin streets again. How can I not? Only this time I will be your guide.

On Oct 24, 2014, at 7:49 AM, Naveen Kishore wrote:

for Martin

I

Invite the visitor with the dark cloak

the wide brimmed hat

and the staff with a twisted handle

into your home

share your food by the fireplace

drink to his health

and yours

let the night be full

of stories

the life you have lived

these so many years

engage the gentleman

in a wide ranging conversation

about life and

death almost

as if you had not guessed

the purpose of his visit

II

He lay dreaming. Still.

As stillness descended.

Like frost. Setting up residence.

On his eyelids.

Unclenching his hand. I freed mine.

Fingers frozen. In cold entrapment.

Silently I placed warmth.

From an open palm.

On eyes full of winter.

Dreaming. I thought.

Of an ancient and distant spring.

For Martin

I am very pleased and honoured to be asked by Esther and Hanna to speak in memory of Martin.

I speak as an old friend. I first met Martin almost 40 years ago. In the days since his death, the sense of deep loss has been difficult to fathom.

I hope these thoughts and reflections connect with yours. I have been thinking of Martin’s walks and what walking meant for him; his journeys and journeying; his love of music and cinema; conversations with him and the last conversations.

* * *

Martin took me on a summer outing to Peacock Island – Pfaueninsel – not long after he had come to live in Berlin and when I was visiting him. It is a very strong memory for a number of reasons. It was such a hot day and in the city the heat hung in the air. It was so cool, by contrast, in the shadow of the large trees on the island. Martin told me of Walter Benjamin’s account of his childhood trip to Pfaueninsel: he had expected to find peacock feathers in the grass and never overcame his disappointment when there were none. We drank pink and green beers. We walked and talked. Time stood still.

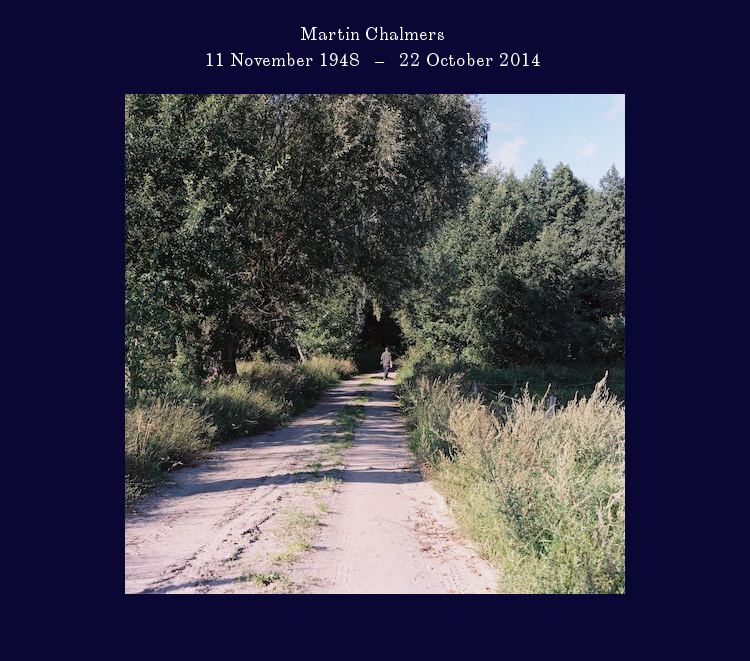

You will all know how much of a walker Martin was. An urban walker and observer; walking as a counterpoint and antidote to a sedentary life among books; walking as a way of getting to know – places, people, books; walking with Esther; walking as a way of being in the world.

* * *

About three years ago I think it was, Martin and Esther went to Angerburgh.

At Angerburgh, deep in the countryside of what is now Poland and was Eastern Prussia, they found the farmhouse where Martin’s grandmother – oma – worked as a serving maid. The journey was part of Martin’s long quest to find out about his history. Oma was the person who looked after him most as a young boy. She only spoke German. At the cinema in Glasgow where they lived with Martin’s mother, he sat next to oma and translated the English dialogue of the films for her.

In different ways different cities have been home to Martin – Glasgow, Birmingham, London, Berlin. But perhaps Glasgow and Berlin more so.

He has written beautiful lines of recollection and observation about both these cities. Many of Martin’s finest qualities as a translator and writer come from a sense of the particular in things and people – the significant detail, the smallest gesture, the use of that word or phrase. A great capacity for empathy – for the exile, for those without a home, for the defenceless.

My thoughts go back to oma.

To little Joey, Martin is opa. Hanna was telling us yesterday about how they walked in the summer holding hands and talking about history – the ancient Egyptians and Vikings, pyramids and longboats. A proud grandfather to Joey and Gabriel, Martin took great delight in the home made by Hanna and Malcolm. He was always devoted to Hanna and I remember how often he used to talk about her, and more recently about ‘the boys’.

* * *

The venue: The Bull pub, Kentish Town, London

The period: Late punk

The band: The Headless Nuns

A night of high decibel music, high energy dancing, by some, considerable heat and little air, many people and little space.

A typical night out with Martin.

A great love of music of many traditions and types characterised Martin’s open and experimental taste. He shared music with Angela in the Glasgow and Birmingham days, and their house was always the hub of new sounds. Hanna was born into this music-filled home, and in one of my first memories of her she is in a buggy at a Rock-Against-Racism event.

Martin was equally an aficionado of cinema. No surprise then that one of the first dates with Esther included seeing Godard’s Alphaville. Wim Wenders was a favourite, especially his Alice of the Cities – Alice in dem Stadten and his

Kings of the Road – Im Lauf der Zeit.

Not by chance they are city and road movies.

One of Martin’s many contributions to making known authors and filmmakers to English-speaking publics were his translation of Brecht’s stories and Alexander Kluge’s essays. It was a great moment when on a visit to San Francisco and to the City Lights Bookshop, there on the shelves was Stories of Mr. Keuner by Bertolt Brecht, translated by Martin Chalmers and in a City Lights Books edition.

Without Martin, we, his friends, are poorer but so are those parts of our culture that are opened up by translation and writing across borders.

* * *

The last conversations. We all remember Martin in our own ways and at different moments. I recently discovered a photo I took of Martin on a trip we made to Berlin. It is 1985 I think. How young we look!

At this time, it is the last memories that are most present and the conversations we have had recently.

Martin loved nothing more than to be with friends and to talk and listen, even when it was physically hard for him to keep going.

‘Yes but you must read Anton Reiser!’

He and Esther were still making plans for when Clare and I were coming – a visit to the Martin Gropius House was planned. We would have talked about the Grunewald altarpiece in Colmar.

Martin was constantly and wonderfully cared for by the paramedics and doctors but also by friends and loved ones. Esther was with him in truly every way possible. She and Hanna were with him at the very end.

It was August when I last saw Martin – a few days of relative relief from the worst afflictions. It was lovely to see the lighted candles on the table and to see Martin and Esther together.

Tribute from Bernhard Sallmann

Lieber Martin,

über Johann Gottfried Seume haben wir kaum gesprochen. Das Gehen war uns zu selbstverständlich als Form eines umfassenden Unterwegsseins, als dass wir ihn im Ausschreiten oder danach im Einkehren hätten nennen müssen. Aber jetzt, für alle, ein Nachtrag. Seume, der von Leipzig nach Syrakus lief und über Paris zurückkam, voll des Lobes für seinen Schuster, schreibt in „Mein Sommer 1805“: „Wer geht, sieht im Durchschnitt anthropologisch und kosmisch mehr, als wer fährt. … Wo alles zu viel fährt, geht alles sehr schlecht, man sehe sich nur um! Sowie man im Wagen sitzt, hat man sich sogleich einige Grade von der ursprünglichen Humanität entfernt. Man kann niemand mehr fest und rein ins Angesicht sehen, wie man soll …. Fahren zeigt Ohnmacht, Gehen Kraft.“

Martin, Dein festes Schuhwerk, dein fester, zurückhaltender, aber auch manchmal schwingender, ja beschwingter Gang. Die Orte haben sich Dir aufgeschlossen, Du hast das Vermögen weiterzugehen wo eine Grenze sein könnte.

Martin, du bist ein „Wanderer“, mehr ein Stadt- als ein Landschaftswanderer. Du bist nicht einmal aufs Fahrrad gestiegen. Du und motorisiert fahrend – undenkbar! Mit Dir konnte ich im vertrauten Berlin unterwegs sein und es anders sehen. Jeder Durchgang, jeder Hinterhof, jede Brache, jede Fassade, jeder Friedhof, jedes Ornament, jedes verblichene Schild, jede Kneipe – es hatte Wert für Dich. Es hat Dir Vergnügen bereitet.

Wir haben uns gefragt wie viele Pferde nach dem Zweiten Krieg in Berlin unterwegs waren. Wo sie standen und wo sie ihr Futter bezogen. Wann sind die Pferde verschwunden aus dem Stadtbild?

Du hast dir, ehe Du in Rixdorf in die Schöneweiderstr. eingezogen bist, zu meinem Erstaunen den Keller zeigen lassen. Du hast Dir vorgestellt welche Menschen während der Bombennächte dort kauerten.

Bei Dir ist der Pol, der ins Vergangene reicht, sehr stark ausgeprägt.

Du bist ein sehr höflicher Mensch. Zuhörend, akzeptierend. Aber mit sehr festen Prinzipien: „Friede den Hütten!“ Das neue Berlin sieht das anders. Du bist ein Hüttenbewohner, ich bin es auch. Da haben wir ähnliche Standpunkte.

Wir werden uns weiter austauschen, lieber Martin!

Bernhard